Sunday, October 25, 2009

Ang Laro Ng Buhay Ni Juan

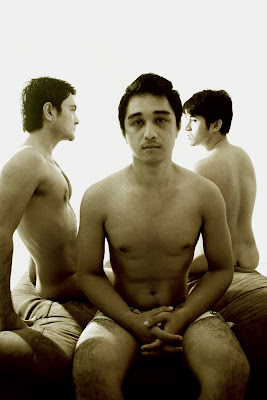

Tony Lopena, Rayan Dulay, Ace Ricafort

The tandem of director Joselito Altarejos and screenwriter Lex Bonife birthed four gay-themed movies for major studio Viva, under its digital arm, starting with 2007's Ang Lalake Sa Parola. With their fifth collaboration, Ang Laro Ng Buhay Ni Juan, the duo make their first "truly independent" film, outside Viva, with Altarejos wearing the producer's hat for BeyondtheBox Productions. With this move, the bigger financial rewards might finally go to the deserving artists, who were anyway responsible for the brand of movie-making that spawned a following. The better news is that the departure seems to have freed them artistically, as well.

The mode is "real time" -- that increasingly fashionable style of storytelling that isolates time and place, an economy of approach well-suited to third world budgets. We follow Juan (Rayan Dulay) during his last hours in Manila, before he permanently leaves for his home province of Masbate. The film is structured in two parts. The first half is daytime, when Juan navigates the slums of his neighborhood, mingling with an assortment of characters, before settling in a tiny room to say goodbye to his lover (Nico Antonio) -- a tender moment that aches so well because we learn so much about the two of them with so little. It's also a positive representation of a same-sex relationship built on mutual love.

Fans might find my next statement blasphemous, but I've always thought that, in the Altarejos-Bonife partnership, the writing was usually the weaker link. Well, so much for that now. Gone are the fussy expositions and purple dialogue that mar their sometimes overly earnest melodramas. Co-written by Bonife, Altarejos, and Peping Salonga, Laro is subtler, but also richer, fresher, more intelligent, if also a little cooler/colder. It's a film that pulsates with the discovery of the moment. Ang Lihim Ni Antonio is its closest forebear, both with naturally flowing existentialism, but this is probably the first time the direction and the writing complemented so effortlessly.

I wonder, however, if the film would have benefited from a more intense lead actor. Real time seems to require a galvanizing, center-of-the-universe presence, the way Gina Pareño held Kubrador, or to a lesser extent, Coco Martin in Kinatay. Dulay is pleasant and effective, but I kind of wish he put more gas to his fire.

The second half is night, as Juan works for one last time as a live sex performer in a gay club, to make extra money for his trip. Here, we meet the kind ringmaster (played by Bonife), a newbie member being oriented, and the rest of the performers, including Juan's cocky partner (Ace Ricafort). The excitement builds up to the actual erotic show, with naked bodies, but the real culmination is... (SPOILER ALERT!) a police raid. What is it that happens to Juan in his last day in Manila? In the answer lies the film's powerful statement.

What the two parts illustrate, before we're even aware of it, is the transfer of money. In Juan's poor community, everyone needs it. But when people part with their cash -- to gamble, to lend to a friend, a lover, someone in need -- it always stems from free choice. What Juan chooses to do with his money is his right and his freedom. We get the spirit of people looking out for one another: It's there when a neighbor shares her plate of noodles, or when the club manager passes a hat and guests drop their generous tokens. By stark contrast, in the final act, when police officers snuff Juan of the contents of his wallet, it's a gross abuse of authority, a trampling of Juan's freedom and dignity. He was robbed of so much more than money. That, according to the film, is the great tragedy of this country. It's what corruption looks like on a micro level, but it extends and affects all of us. No coincidence, then, that our hero is called Juan, the name of the everyman.

Laro is the second excellent film this year to indict the illegal, inhumane practice of police raids. (Big Night was the other one.) The topic demands attention, and both films are must-sees. That Laro drives the important point with quiet grace is amazing.

GRADE: A-

The mode is "real time" -- that increasingly fashionable style of storytelling that isolates time and place, an economy of approach well-suited to third world budgets. We follow Juan (Rayan Dulay) during his last hours in Manila, before he permanently leaves for his home province of Masbate. The film is structured in two parts. The first half is daytime, when Juan navigates the slums of his neighborhood, mingling with an assortment of characters, before settling in a tiny room to say goodbye to his lover (Nico Antonio) -- a tender moment that aches so well because we learn so much about the two of them with so little. It's also a positive representation of a same-sex relationship built on mutual love.

Fans might find my next statement blasphemous, but I've always thought that, in the Altarejos-Bonife partnership, the writing was usually the weaker link. Well, so much for that now. Gone are the fussy expositions and purple dialogue that mar their sometimes overly earnest melodramas. Co-written by Bonife, Altarejos, and Peping Salonga, Laro is subtler, but also richer, fresher, more intelligent, if also a little cooler/colder. It's a film that pulsates with the discovery of the moment. Ang Lihim Ni Antonio is its closest forebear, both with naturally flowing existentialism, but this is probably the first time the direction and the writing complemented so effortlessly.

I wonder, however, if the film would have benefited from a more intense lead actor. Real time seems to require a galvanizing, center-of-the-universe presence, the way Gina Pareño held Kubrador, or to a lesser extent, Coco Martin in Kinatay. Dulay is pleasant and effective, but I kind of wish he put more gas to his fire.

The second half is night, as Juan works for one last time as a live sex performer in a gay club, to make extra money for his trip. Here, we meet the kind ringmaster (played by Bonife), a newbie member being oriented, and the rest of the performers, including Juan's cocky partner (Ace Ricafort). The excitement builds up to the actual erotic show, with naked bodies, but the real culmination is... (SPOILER ALERT!) a police raid. What is it that happens to Juan in his last day in Manila? In the answer lies the film's powerful statement.

What the two parts illustrate, before we're even aware of it, is the transfer of money. In Juan's poor community, everyone needs it. But when people part with their cash -- to gamble, to lend to a friend, a lover, someone in need -- it always stems from free choice. What Juan chooses to do with his money is his right and his freedom. We get the spirit of people looking out for one another: It's there when a neighbor shares her plate of noodles, or when the club manager passes a hat and guests drop their generous tokens. By stark contrast, in the final act, when police officers snuff Juan of the contents of his wallet, it's a gross abuse of authority, a trampling of Juan's freedom and dignity. He was robbed of so much more than money. That, according to the film, is the great tragedy of this country. It's what corruption looks like on a micro level, but it extends and affects all of us. No coincidence, then, that our hero is called Juan, the name of the everyman.

Laro is the second excellent film this year to indict the illegal, inhumane practice of police raids. (Big Night was the other one.) The topic demands attention, and both films are must-sees. That Laro drives the important point with quiet grace is amazing.

GRADE: A-

No comments:

Post a Comment